Synopsis

Short Synopsis

Award-winning filmmaker Min Sook Lee searches for memories of her mother, Song Ji Lee, who died by suicide when Lee was 12 years old. A looming figure in this search is Lee’s now 90-year-old father, who met her mother while serving in a national intelligence agency under dictator Park Chung Hee in 1960s South Korea. Through a fabric of real and imagined histories, Lee reveals that some stories must still be told, even when the words are forgotten.

Long synopsis

Award-winning filmmaker Min Sook Lee turns the camera on herself in this urgent documentary, searching for memories of her mother, Song Ji Lee, who died by suicide when Lee was just 12 years old.

Confrontational and speculative, There Are No Words contemplates how trauma fractures memory as Lee revisits the people and places of her childhood in Toronto, Canada, and Hwasun, South Korea, her place of birth.

A looming figure in this search is Lee’s now 90-year-old father, who met her mother while serving in a national intelligence agency under dictator Park Chung Hee in 1960s South Korea. He is her last direct connection to her mother, although he’s an unreliable narrator with a history of abuse who speaks in a mother tongue she cannot fully understand.

Through a fabric of real and imagined histories, Lee reveals that some stories must still be told, even when there are no words for grief.

Q&A with min Sook Lee

-

Description teNo, the joy of making a documentary is the process. You don’t know what you’re going to be making until you set out, and if you did think you knew, then what would be the point?

You’re setting out on a journey that’s very important to you, and you have some guiding questions, but how you’re going to take that journey isn’t clear. So it’s process-driven, and you have to trust. These things are like brambles along a trail; paths get cleared as you do it. The film revealed itself to me in the editing suite. You might have 50 to 60 hours of footage and have to whittle it down into 90 minutes. You discover the film in that process, and that’s the film that was waiting for you.

Most importantly, no film is complete until you’ve had a screening. I understand that more now with this film.xt goes here

-

Description text goEvery project has its defining approaches and tools. With this one, I set out wanting to tell a personal story: to look at and understand the relationship with my mother and father, the limits and constraints of my mother’s life, who she was as a human and how she exercised agency, resistance and rebellion. A person like my mother was never scheduled to be remembered. She was scheduled to be forgotten.

What is my role here in making this project and looking at a part of my own family story? How do I think about it as part of a public story, as all our stories are? How can I understand how we remember through the fog of history?

Dionne Brand writes about wanting to sit in the room with history at the beginning of A Map to the Door of No Return. It is such a beautiful metaphor, but you also know that when you do that, you may have to sit with many atrocities, abuses or unspeakable actions that have happened and you now have to engage with. It is an image I have held often. But it also reminds you that nothing is ever over. The past is always in the present.es here

-

One of the first things I wanted to do as soon as I knew the film was happening was to see a mudang. Mudangs allow us to explore an expression of grief that feels uniquely Korean. They demonstrate a belief in animism. I know that’s true to who I am, and it is an inheritance from my mother. Once I was able to be there with the land, the rocks, the trees, I understood the power of that.

It is interesting that during the ceremony itself, I didn’t feel comforted. I was cold, tired and aware that it was six hours long. I had to contend with the weather and a camera crew. All those external conditions of shooting were very much on my mind, so I wasn’t lost in this shamanistic ritual. I was very conscious that the camera was on me, and I was thinking about what I was supposed to do.

But in the editing suite with Yong (editor), all the hyper concerns faded away as I started cutting the material. Filmmaking allows us to live twice. You live once in your world, and then again in the film world you’re making. Making and reshaping the material into what you think happened, or a semblance of what you want to pay attention to. When I view the mudang scenes now, I feel a strong sense of the spiritual power that the kut [the ritual performed by the mudang] builds.

-

During the pandemic, I felt this compulsion to go visit my father. I would go with my kids and partner. We’d call and wave to him. I needed to do that, and I did that repeatedly in the first days of the pandemic. I remember thinking, “Wow, you’re not very close to him, why are you bereft? Why are you so terrified he’s going to die?” Then I realized, I was deeply in anguish that he might die. “Oh, you’re grieving your mom. If he dies, she’s gone forever.” That she might be expunged from the public narrative made me feel desperate. I wanted her memory to be alive, to give life back to myself and her. There is a cultural belief that a person dies permanently once their memory is erased. By speaking their name, you are resurrecting them in a way.

How do you protect yourself? You think about the people who are surrounding you for the next two to five years. I’d never worked with Yong before, but he was the first person I reached out to. I was in Galleria Shopping Centre when I called to describe my story, and asked him, “Do you think this is a film?” He so wholly saw and understood. He was 100 percent committed. There was something about his energy that I wanted to be around. He was also fully fluent in Korean.

Iris Ng (cinematographer) is someone I’ve built a long working relationship with. She brings a poised stillness to her filming. She holds the camera with so much grace, and captures the enormity of a personhood, and the magnitude and quietness of the moment. She has this sensitivity to the psychological space of the people in a room. With her camera, she is exactly where she needs to be.

As you’re going through the process, you also have a circle of friends, peers and teachers you’re talking to. You’re reading the writers. I have a very good therapist. My family held space for me differently. I took such pleasure being with my children while filming because it offered me a new dimension of love and joy that I didn’t have with my mother: love and pain, love and fear, love and sadness.

Excerpts

"Can I lie a little?"

The Store

A loss of a different kind

Images

Min Sook Lee

Min Sook Lee

Min Sook Lee

Min Sook Lee

The store

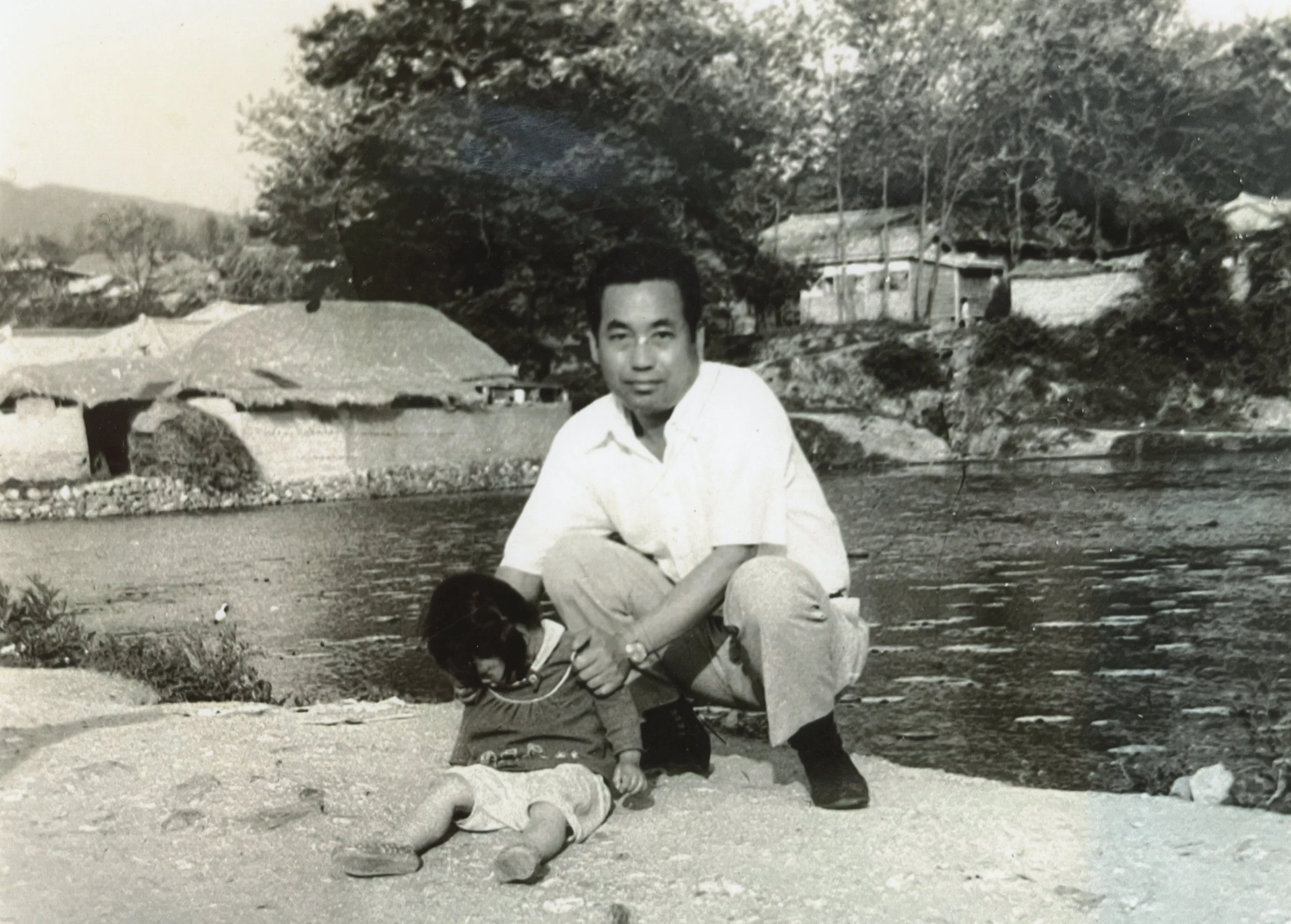

Min Sook Lee and her mother, Song Ji Lee (July 16, 1980)

Min Sook Lee sits across from her father (production still)

Min Sook Lee sits across from her father (production still)

Min Sook Lee and her father, Chung Beum Lee